European Commission has adopted new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU. We ask Virginijus Sinkevičius, EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries about the role of offshore wind as well as how to coordinate renewables development in the Baltic Sea region while taking into account environmental protection.

Although the living resources, non-living resources, port activities and maritime transport sectors suffered strongly, they are all foreseen to recover promptly. In contrast, coastal tourism, which suffered particular hardship from the pandemic, is likely to have a lagged recovery path. Shipbuilding is also expected to have a slower, lagged recovery. Finally, most of the emerging sectors suffered small overall impacts in 2020 and are all expected to recover swiftly.

The EU has adopted an ambitious recovery package of some 750 billion euro, which aims to make the EU greener, more digital, more resilient and better fit for the current and forthcoming challenges. The new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU tabled on 17 May 2021 will play an important role. The blue economy suggests solutions from the sea that will help to deliver the European Green Deal. Marine renewable energy can help us to reach our targets in terms of reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. While some technologies are mature, others need further support to reach commercial stage. In the same way, the sea could produce alternative sources of proteins and that is why the Commission is preparing a specific initiative to boost algae production in the EU.

On the other hand, all the blue economy sectors needs to increase their efforts to transition to more sustainable practices and notably decarbonise their activities. Look at the maritime transport for instance. The European Green Deal calls for a 90% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from all modes of transports and this includes maritime transport. We need also to invest in more circularity and this applies to the offshore wind industry that should develop decommissioning schemes for wind turbines.

The blue economy should benefit from the EU recovery and resilience funds. But public funding alone is not enough. The Commission and the European Investment Bank will continue to advocate for sustainable blue economy finance principles with private investors, arguing that choosing sustainability will create tangible opportunities for new jobs and businesses. To address the specific needs of blue economy SMEs, the Commission’s BlueInvest Platform provides them with customised support, visibility, access to investors and investment-readiness advice. The BlueInvest equity fund will combine financial contributions from the EU budget with private venture capital to finance blue tech start-ups.

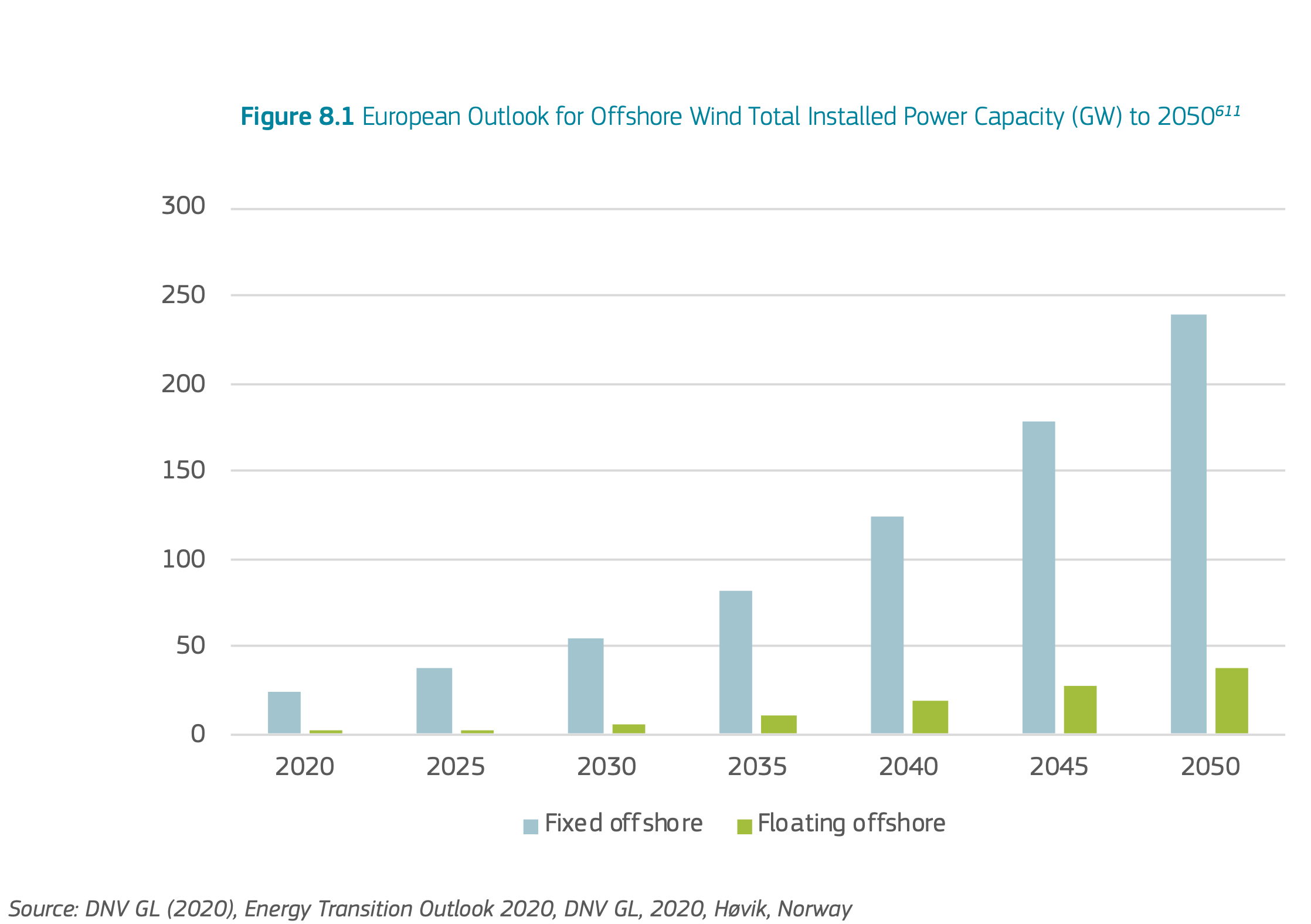

When we look at offshore renewables, the EU is already a global leader in bottom-fixed wind turbines with large commercial-scale projects currently operating. The EU has the most ambitious targets worldwide for the coming years, as set out in the offshore renewable energy strategy (300GW by 2050 – combined bottom-fixed and floating wind). Certain sea-basins do not have the geophysical conditions to host large bottom-fixed wind farms, such as the Mediterranean Sea. In the Baltic Sea in contrast, the potential for offshore wind energy production is high: more than 90 GW.

Source: The EU Blue Economy Report 2021, European Commission.

Baltic Member States have understood well the need to explore further this potential and signed a joint declaration of intent in September 2020 with the aim of increasing offshore wind electricity supplies.

Shipping companies and ship designers are also looking to green technologies and for sustainable alternatives to traditional fuel. Green hydrogen can be produced from renewable energy and therefore is easily coupled with offshore wind electricity production. The offshore renewable energy strategy encourages Member States to consider hydrogen production and transport in grid planning. In addition, new models of vessels using wind as the main propulsion are also under development.

How to coordinate the offshore wind development with environmental protection? What in particular should be taken into account in the Baltic Sea region?

Both the offshore renewable energy strategy and the new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU insist on the importance of coherently addressing climate change and biodiversity objectives. All projects, as ambitious as they are, must comply with environmental legislation and we need to plan in advance for co-existence between nature protection and energy generation.

Maritime Spatial Planning has a central role to play in steering this practice of multi-use of maritime space, by delineating areas where offshore is encouraged to happen. Through the Maritime Spatial Planning process, different ministries and stakeholders have to sit together and discuss future developments at sea, including offshore renewable developments. To support Member States, the Commission developed a specific guidance document on wind energy development and nature legislation, which accompanied the publication of the offshore renewable energy strategy. In addition, the Commission committed to promoting a dialogue on offshore renewable energy between public authorities, stakeholders and scientists in the form of a community of practice, which will tackle potential for multi-use, especially with nature protection and restoration.

In the Baltic Sea, there are already good examples of multiple uses of offshore wind farm areas with other sectors such as aquaculture and tourism, notably in Denmark with a project allying tourism, citizens involvement in energy production and offshore wind. We want to see more best practices of nature protection and energy production emerging in the coming years.

Thank you